March 2021

International Students in the U.S. Higher Education

March 30, 2021

More than one million international students are enrolled in postsecondary institutions in the U.S., representing 5.5% of the entire college student body. International students have been in the spotlight for topics such as immigration policy changes, financial and economic contributions, discrimination and stereotypes, etc. Higher education leaders and policymakers are keen to learn the enrollment trends and their policy implications. Student affairs professionals are tasked to address challenges faced by international students, both before and after their arrivals.

Why do International Students choose to study in the U.S.?

More than 80% of the international students came to the U.S. to earn a postsecondary degree. Most international undergraduates pay the higher, non-resident tuition rate. Some institutions add an international fee on top of the non-resident tuition, making international students the premium group to recruit with respect to revenue.

International students often balance cost with benefit, before coming to the U.S. to further their education. That is, if the benefits (e.g., getting a degree in the U.S.) are greater than the costs (e.g., cost of education and living), an international student may choose to study abroad; vice versa.

Once arrived, international students are usually more motivated to focus on getting a bachelor's degree or beyond than domestic students as they are more invested in this journey and have fewer other options to thrive.

Three major reasons for international students to study in the U.S.:

- U.S. has a better higher education system.

- A wide range of institutions and programs in the U.S. that can fit their diversified needs.

- Graduates of U.S. higher education institutions earn the opportunity to establish and expand career via immigration.

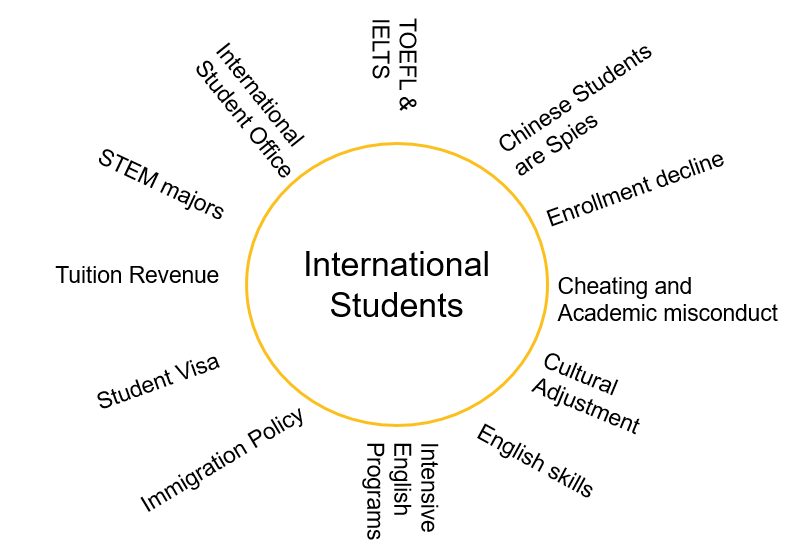

Emerging themes and topics about international students

In fall 2020, I organized a class activity asking a group of higher education major

students to brainstorm about general themes and topics about international students

currently enrolled in the U.S. Here is a summary of the themes and topics that they

came up with: TOEFL & IELTS; Chinese Students are Spies; Enrollment Decline; Cheating

and Academic Misconduct; Cultural Adjustment; English Skills; Intensive English Programs;

Immigration Policy; Student Visa; Tuition Revenue; STEM Majors; and International

Student Office.

This narrative presents several facts about international students in the U.S., including enrollment trends, motivations of study abroad, challenges and discriminations, and more.

Facts and Trends

From Academic Year(AY) 2006-2007 to AY 2017-2018, international college student enrollment in the U.S. increased from 582,948 to 1,094,792. However, a decrease was observed in AY 2019-2020, the first time over the 15-year time span. The COVID-19 pandemic and its related travel and immigration policies were responsible for this decrease. As many institutions moved into online instruction, international students face difficulties (e.g., visa) in traveling to the U.S. Attending online classes in their home countries was also challenging because of the time zone differences, access to the technology, and competing domestic opportunities.

China has been the leading place of origin for international students studying in U.S. universities and colleges since AY 2008-2009. In AY 2019-2020, Chinese students represented 34.7% of the overall international enrollment in higher education. Of all international college students, 77.5% majored in STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math) fields. In AY 2019-2020, 45% of the new international students enrolled in a graduate program compared to 40% in an undergraduate program.

CHECK OUT MORE RESOURCES AND TRENDS FROM THE INSTITUTE OF INTERNATIONAL EDUCATION

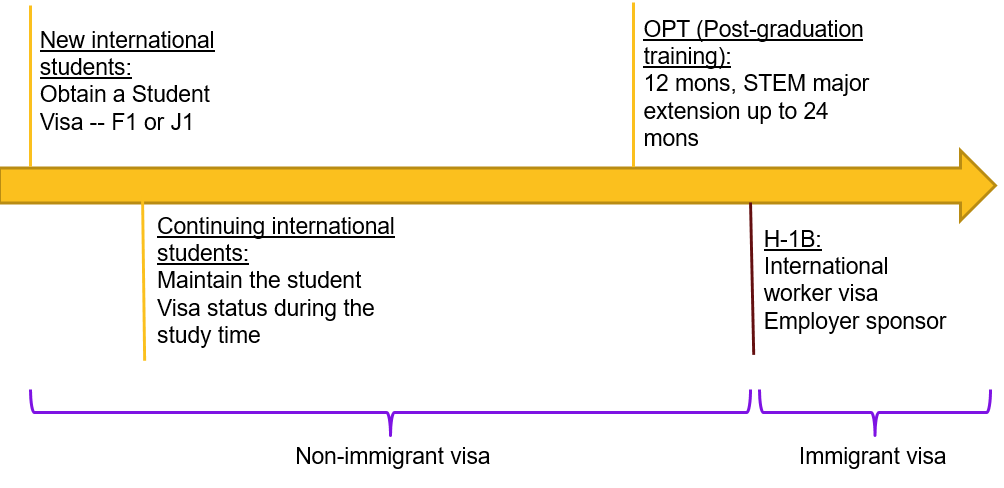

How does Immigration Policy Influence International Enrollment?

Every international student has to obtain a student visa (either an F1 or a J1 visa) before entering the U.S. The visa policy has been serving as a gatekeeper for foreigners. For example, the 9/11 policies emphasized the screening of student visa applicants, where applicants had to wait for a longer time to obtain a student visa. Students in certain STEM majors had to go through additional screening procedures. This was seen as a major concern for many prospective international students, which caused a temporary drop in enrollment of international students in AY2011-2012. More recently, in 2017, President Trump issued a travel ban affecting students from Iraq, Syria, Iran, Libya, Somalia, Sudan, and Yemen to enter the U.S. This decreased the new international enrollment by 3.3% (Redden, 2017).

Many international students seek better career opportunities upon graduation. Policy changes on employment visas (such as the H-1B visa program) greatly impact international enrollment. For example, a 2003 policy change added a nationality-based cap on the H-1B visa. This reduced the H-1B visa issuance from 195,000 to 65,000. Economic studies proved that this dramatic drop in H-1B visas impacted both the quantity and the quality of international enrollment (Shih, 2016; Kato & Sparder, 2013).

International enrollment and visa policy

New International students:

Obtain a Student Visa - F1 or J1

Continuing international students:

Maintain the student Visa status during the study time.

OPT (Post-graduation training):

12 months, STEM major extension up to 24 months

H-1B:

International worker visa

Employer sponsor

Post-arrival Transition and Challenges

Upon arrival, international students need to transition to a new environment:

- from being a high school student to a college student, or from an undergraduate to a graduate student;

- from their home countries to a foreign country, many of who have to learn a new language and adjust to new culture.

The majority of the international students take a language test, such as TOEFL and IELTS, before being admitted to a degree program. However, a sufficiently high score on these English tests does not always transfer to high confidence in conversing in and beyond the classroom. Also, some international students, especially those from East Asian countries, often find it challenging to adjust to the Western learning style. They are used to viewing their instructors as a guru who should never be challenged. They are hesitant to present their ideas opposing others’ opinions to “save face” as they wish to maintain harmony (good relationship) with others. These cultural nuances and backgrounds explain why some East Asian international students choose to sit quietly in the classroom and not actively participate in class discussions.

As a recent stereotype, many international students might be mis-regarded as kids from wealthy families who can afford the expensive tuition and fees. However, regardless of their social-economic status in their home countries, the vast majority of international students are new to a U.S. college campus. Their parents are unlikely to provide any advice on how to survive and thrive in a U.S. college. In fact, when facing difficulties and challenges, international students often choose to hide the truth from their parents and try to solve the problem on their own, so they would not make them worried (Chen, Li, & Hagedorn, 2020).

Many international students are non-White or racial minorities. They suffer from the same discrimination against students of color. Unlike their domestic counterparts who are the majority at their home country, many international students have limited knowledge and experiences about discrimination. Due to the language barriers, they might not fully understand the racial jokes and slurs. Further, they may not know how to respond to these problems and where to seek support.

There are also discrimination and hostile acts particularly targeting international students. In 2017, a group of Chinese students at Columbia University found their name tags ripped off from the doors of their dorm rooms. They were targeted simply because of their Chinese names. These students fought the racist acts by making a short video telling people the meaning behind their Chinese names.

More to Read:

Chen, Y., Li, R. & Hagedorn, L. S. (2020). International reverse transfer students: A critical analysis based on field, habitus, social and cultural capital. Community College Review, 48(4), 376-399. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/0091552120932223

Chen, Y., Li, R. & Hagedorn, L.S. (2019). Undergraduate international student enrollment forecasting model: An application of time series analysis. Journal of International Students. 9(1), 242-264. DOI: https://doi.org/10.32674/jis.v9i1.266

Institute of International Education. (2020). The Open Doors Report on International Educational Exchange. https://www.iie.org/Research-and-Insights/Publications/Open-Doors-2020

Kato, T. & Sparber, C. (2013). Quotas and quality: The effect of H-1B visa restrictions on the pool of prospective undergraduate students from abroad. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 95(1), 109-126. https://doi.org/10.1162/REST_a_00245

Redden, E. (2017). New international enrollments decline. Inside Higher ED. Retrieved from https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2017/11/13/us-universities-report-declines-enrollments-new-international-students-study-abroad

Shih, K. (2016). Labor market openness, H-1B visa policy, and the scale of international student enrollment in the United States. Economic Inquiry, 54(1), 121-138. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecin.12250

Written by: Yu "April" Chen, PhD

Dr. Yu “April” Chen is an assistant professor in the School of Education at LSU. Her

research primarily focused on community college student success, international students,

and STEM pathways for underrepresented minorities.