MC 3005 In-Depth Reporting

MC 3005 is a journalism class where students learn strategies for gathering and analyzing information and data that include traditional and digital public records, databases, and government documents to produce in-depth and investigative reporting projects. The following stories from the class have been published by professional news outlets across Louisiana.

Our Stories

‘We’re not done yet’: Businesses key in preserving Cajun culture

By Jillian Elliott, Layne Miller and Taegen Heck - 07.12.2023

When Alex Cook stumbled on a flyer for a local juke joint, he was confused about how he, a member of the Baton Rouge music scene, was unfamiliar with a spot just minutes away in Zachary.

This first visit sparked dozens of features in Cook’s 2012 book, “Louisiana Saturday Night: Looking for a Good Time in South Louisiana’s Juke Joints, Honkey-Tonks and Dancehalls.”

But what he intended to be a travel guide is now a last look at places on a growing list of family-owned Cajun businesses that have closed.

Read more at Lafourche Gazette.

Louisianans have sought to tame the Mississippi River for decades. Now they may set it free.

By Oscar Tickle - 10.26.2022

POINT À LA HACHE – Don Beshel walks out of his office and looks out on his marina. Where once were dozens of boats now sit only a few. The levee has more boats washed up from flooding than line his docks.

The air here used to have salty undertones. Now fresh water from the Mississippi River has mixed with salty water from the Gulf. The air is now stale – along with Beshel’s business.

He blames a breach in the levee downriver back in 2011. Before the breach, oysters and saltwater fish like mullet thrived around his marina. Now the water brims with different kinds of fish. The old marsh is gone, replaced by a nearly unrecognizable landscape lined with rows of black-willow trees. Boats cannot find their way out of the marsh due to silt dumped by fresh water from the breach.

Read more at LA Illuminator.

These Louisiana cities saw a surge in murders as police struggle to close cases.

By Lara Nicholson, Zane Piontek, Brea Rougeau and Jada Hemsley - 01.03.2022

Chlanda Gibson was in her bed last April when she heard loud pops outside her window.

She had fallen asleep while waiting for her son, 17-year-old Roddrick Cook, to come home after going out with friends. When she went to check on the noise, his friends knocked on the back door for help — one with a gunshot wound in his leg.

Cook was nowhere to be found, and as police investigated, Gibson sat in the back of a police cruiser, where she spent five dark hours wondering what had happened to him. Then she was given the devastating news: Her son, the 6-foot 4-inch, 250-pound high school football player who dreamed of going to the NFL, had been killed that night.

Read more at WWNO.

LSU students uneasy as robberies, car burglaries increase

By Alaina A. Alfred, Alejandro Burgos and Taylar R. Green - 12.27.2021

Living in an LSU dorm, Jack Tomeny is used to leaving his car unattended in a campus lot for a few days at a time. One day Tomeny noticed that someone had stolen his backpack from the backseat along with the loose change he had in the car.

Tomeny fell victim to a recurring theme that is making students uneasy not only on campus but at popular student apartment complexes near the LSU campus.

The number of car break-ins reported on campus jumped to 22 during this fall semester alone after falling to just two while students were studying remotely in 2020 and averaging 10 a year in the three years before that.

Read more at HoumaToday.

Pros and cons: How Louisiana college students were impacted by online learning

By Masie O'Toole, Kirby Koch, Donald Fountain - 12.23.2021

Bryce Trum sat up in his twin-sized bed at 6:55 a.m. His day of classes at LSU was about to start at 7 a.m., and his classroom was only five feet away.

But as he signed onto the Zoom meeting on his computer, his attention was immediately drawn to his guitar.

Six strings were all it took to draw his eyes away from the task at hand. Six strings on his acoustic guitar leaning up against his eggshell white walls became more enticing than listening to the voice coming through the Alienware laptop on his desk. The instrument created an easy distraction for Trum, and avoiding his online computer science class became second nature.

Read more at the dailycomet.

As industries decline and storms intensify, Louisiana's small towns shrink

By Caden Lim, Joe Kehrli, Logan Puissegur and Alexander Sobel - 12.22.2021

Every morning, Floyd Dupre and his son, Mike, button up their denim shirts, throw on some jeans and slip into their boots. It’s another day on the farm tending to their cattle.

Meanwhile, 60 miles east in the state’s capital, Floyd’s grandson and Mike’s nephew Joseph Dupre hits the gym near his apartment and heads to class at the state-of-the-art engineering building on LSU’s campus.

Joey Dupre is a chemical engineering student who wants to focus on sustainable energy sources. He aspires to live in Houston rather than take over his grandfather’s farm, and his story is typical for rural Louisiana, where younger generations are leaving for more opportunities in urban areas and other states.

Read more at the Gonzales Weekly Citizen.

'It's very discouraging': Louisiana teachers grapple with challenges of ongoing pandemic

By Margaret DeLaney, Olivia Varden and Chris Langley - 12.21.2021

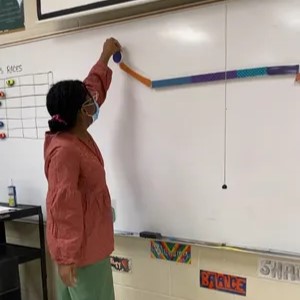

In fourth-grade teacher Laura Spurgeon’s class, the students who attended school in person during the pandemic sit in one area, and those who were online last year sit in another. A third group, the students still working from home, join on a screen.

“It’s like I’m teaching three different levels instead of one,” Spurgeon said. “The students who still stay at home ‘sick' and have to join via Zoom, the ones that opted for online last year and didn’t learn as much, and the kiddos who have been in person the entire time.”

Teachers, administrators and counselors are trying to figure out how to help many students catch up and get K-12 education back on track. However, they must determine how to reach students who are now performing at different levels while also dealing with the psychological fallout on children who had limited social contact during the shutdowns.

Read more at the Shreveport Times.

Stay or go? Louisiana residents are being forced to face climate crisis threats

By Joe Rizzo, Joey Bullard and Michael Sanders - 12.20.2021

As Hurricane Ida rapidly grew in strength, crabbers Stacia Johnson and Justin Smith were left with just three days to relocate their $100,000 supply of crab traps. Knowing the traps could be severely damaged or stolen if left on land, the siblings dropped their traps in the Biloxi Marsh, said a prayer and evacuated to Arkansas. Days later, unsure how many traps would be left, they found that not only were all of the traps intact, but they were also filled to the brim with crabs.

Johnson called the event a miracle in a string of unfortunate events due to the worsening effects of climate change. Rising water temperatures, disappearing islands and rapidly changing salinity levels have severely altered their fishing routes and the migration patterns of the crustaceans they catch. These changes have significantly hindered their success as commercial fishers.

The Johnson-Smith family is not alone. As ocean temperatures rise, hurricane seasons become longer and more intense, and residents across the state are being forced to face the existential threats of the climate crisis.

Read more at the Shreveport Times.

Segregated customs remain in some Louisiana cemeteries

By Allison Kadlubar, Bailee Hoggatt and Ezekiel Robinson - 05.10.2021

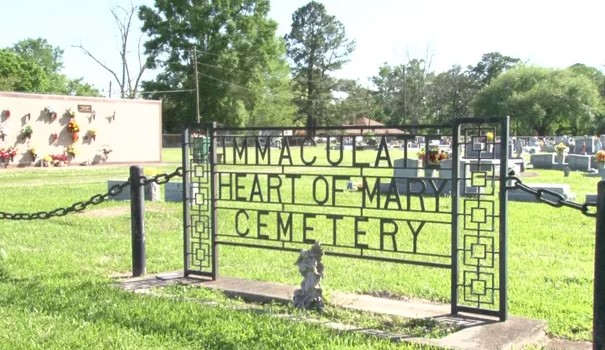

BATON ROUGE — Jessica Tilson spent many Sunday mornings in the early 1980s playing outside with her white friends under the shady oak trees in front of the fleur-de-lis stained glass windows of the Immaculate Heart of Mary Church in Maringouin. But as soon as the church bells rang, they parted.

“When it was time to go into the church, it was time to split up,” Tilson said.

The church has a main entrance with double doors, but members typically enter through separate doors on the sides of the building — to the left for Black members, to the right for white members. Once inside, Black and white members sit on opposite sides of the sanctuary to worship in front of one altar — even though Tilson said the church abandoned formal segregation in the 1980s.

Immaculate Heart of Mary Cemetery also divides graves by skin color on the left and right sides of the main pathway mirroring the church practices. The right side presents a spacious, organized pattern of granite and marble tombstones. The left side is crowded and scattered as many present-day graves are layered on top of people who, in life, were enslaved.

Read more at the Daily Advertiser.

'I couldn’t move my legs' The concussion danger in Louisiana youth football

By Hunter M. McCann, Keith A Fell Jr., Anthony J. Mocklin, Jessica Speziale, Henry Weldon - 01.15.2021

Lance Garafola lay on the turf of a high school football field wondering what had happened and where the feeling in his lower body had gone. The crowd and both sidelines fell silent as trainers rushed onto the field.

Garafola was a sophomore at St. Michael the Archangel High School in 2016 when a Loranger High player blind-sided him on an onside kick. Paramedics were brought in when Garafola said he couldn’t feel his legs, but they were hesitant to move him because of the possible severity of his injury. Silence and fear hung in the air for over an hour before they raised him onto a stretcher and Garafola threw up his thumb to let his teammates and fans know he was conscious.

He was taken to a local hospital and diagnosed with a concussion. The loss of feeling in the lower half of his body, which lasted for a little over 5 minutes, was created by the concussion and the shock from the hit to his head.

Nearly every football fan knows that concussions are a serious problem in the NFL and in college games, but less attention has been paid to the dangers facing younger athletes. Experts say high school players also face some degree of risk every time they step on the field.

Read more at WWLTV.

'Russian roulette of drugs': Fentanyl-related deaths on the rise in Louisiana

By Evan Saacks, Myles Kuss and Eric Brasher - 04.25.2020

Graham Jordan, a 21-year-old LSU student, did not wake up one morning after partying at a bar in the Tigerland area near campus in 2017. The autopsy showed that Xanax had been in his system, but a deeper observation showed something much worse — traces of fentanyl, a dangerous compound that street dealers mix into other drugs to increase the high.

Fentanyl is an opioid that doctors use to treat severe pain. But it is so powerful, and it is becoming so common as an added ingredient in street drugs, that it is responsible for more than half of all opioid overdose deaths in some parishes.

Jordan, the LSU student, died after taking Xanax laced with a lethal amount of fentanyl. Mary Ellen Jordan knows fentanyl was not a drug her son sought out.

“I had never even heard of it before we got his autopsy report,” she said. “I don’t really think most people take that on purpose.”

Read more at the Town Talk.

'It is so dangerous': Vaping epidemic leaving students concerned for their health

By Ava Perego, Raymond Constantino, Kristen Singleton and Falon Brown - 12.12.2019

BATON ROUGE — One LSU student walked through security and ID checks to purchase a legal vape cartridge filled with cannabis oil in Los Angeles. Another walked up to the back of a van off a dimly lit road somewhere in Louisiana to buy one illegally; no ID checks, no security and no certainty that the purchase was safe.

This is the reality of the so-called THC black market in Louisiana, the local part of the nationwide scare over deaths and illnesses related to vaping. THC, or tetrahydrocannabinol, is the psychoactive chemical in marijuana that causes users to get high.

The Louisiana Health Department reported that the state now has more than 30 cases of lung injury — and one death — associated with vaping a combination of THC and nicotine. The combination of both substances contributed to 55% of the illnesses, more than the reported illnesses caused from both nicotine and THC independently.

Read more at the Daily Advertiser.

Letter to the editor: 'Racist' Tigerland dress code unlikely to change unless call to action taken

By Ashlon Lusk and Walter Miller - 12.06.2019

The bars on the edge of LSU’s campus have been accused of having a racist dress code and enforcing it on mostly men and people of color.

This strip of bars is called Tigerland. It is a popular spot for college students to go to and attending is part of University tradition. They are like any other college bar: dirty, sloppy and full of drunk college-aged patrons. Almost no one would call these bars upscale, so why do they enforce a dress code?

In 2003 the NAACP encouraged a boycott of Tigerland, located on the corner of Nicholson Drive and Jennifer Jean Drive. The bars were still full the day of the boycott. I don’t think things would be different today. The usual patrons of the bar are white fraternity and sorority members. The dress codes don’t affect this demographic.

Read more at the Reveille.

College football brings many families together, but takes its toll on families of coaches

By Tanner Craft, Tyler Eschette, Grayson Miller and Kristen Payne - 11.25.2019

NATCHITOCHES - Northwestern State had the Bears on their heels on Oct. 19, looking to erase an 0-6 start to the season. Just nine yards separated the Demons from potential overtime with No. 13 Central Arkansas.

Demons quarterback Shelton Eppler took the snap, dropped back and found a receiver in the back of the end zone. Now the decision: Go for two and the win, or play it safe and go to overtime? Easy choice for a coach who is trying to turn his program around – go for two.

At the 50-yard line, six rows up in the stands, Renee Laird, the wife of head coach Brad Laird, waits, hands clasped nervously around her face, for the most dramatic moment of the season to unfold.

Eppler drops back again and sees his receiver with a step on his defender. But the pass gets knocked away, and Renee Laird collapses in disappointment, undoubtedly feeling the same raw emotion as her husband.

Coaches and their families go through many stresses, no matter the sport, and Renee Laird’s reaction illustrates how difficult it can be to weather the ups and downs. Whether it be the never-ending pressure of building a program or the time that coaches spend away from home, the impact is the same. And in recent interviews, Mrs. Laird and Northwestern State coaches described the emotional roller-coaster that they and their families are often on.

Read more at the News Star.

In light of #MeToo movement, more students seeking support

By Claire Bermudez, Caroline Fenton and Payton Ibos - 12.04.2018

Following the #MeToo movement and the hearings on Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh, more women are coming forward on Louisiana college campuses with complaints of sexual assault and relationship violence.

LSU’s Lighthouse counseling program received 91 requests for support last year, up from 53 in 2016. During the September showdown between Kavanaugh and a woman who accused him of having assaulted her when they were teenagers, requests by LSU students for counseling increased to two a day.

“When the #MeToo initially came out, a lot of our accredited sexual assault centers throughout Louisiana did see a surge in hotline calls,” Josef Canaria, LaFASA’s campus sexual violence coordinator, said. “Statewide, our rape crisis centers phone lines were off the hook.”

Read more at the Daily World.

41 pedestrians have been hit on LSU's campus in five years

By Britt Lofaso and Kennedi Walker - 11.28.2018

Mari Dehrab was standing near a crosswalk on her way to class at LSU when everything went black. A car had careened onto the sidewalk and smashed into her and three other pedestrians before slamming into a light pole. Screams filled the air as she landed several feet away.

Dehrab, 23, suffered a brain tear, causing memory loss so severe that at one point, she could not remember some of her family members. One of her ankles was broken and the other sprained, confining her to wheelchair for six weeks. She had to drop out of school this semester, making it impossible for her to graduate in the spring.

“I went through such a big depression, and I still have depression,” she said, adding that “my life has been put on pause because of this accident.”

“I feel like I’m not as whole as I used to be,” she said.

Read more at the Daily Advertiser.

Mind and body: How do Louisiana colleges help athletes maintain their mental health?

By Dylan Alvarez, Brennen Normand and Jace Mallory - 11.28.2018

As a former collegiate gymnast, Lauren Li, found comfort at LSU after experiencing emotional distress at Penn State.

“Anxiety, depression, eating disorders: It was tough just talking about it because being used to suppressing those emotions,” said Li, who was on LSU’s highly ranked team over the last three seasons. "I had to, like, learn how to be comfortable talking about it and seeking help for it if I wanted to help myself."

It is no secret that expectations are high for athletes at universities across the country. These pressures take a toll, emotionally and physically, on athletes in all sports. And there has long been a stigma that discourages many of them from seeking mental and psychological help.

But now schools in Louisiana and elsewhere are doing more to address the problem, thanks in part to guidelines that the National Collegiate Athletic Association created in 2016 to encourage them to address the problem.

Read more at the Town Talk.